Borderline Personality Disorder, Spiral of Violence, Murder and Concealment of the Body

Bernat N Tiffon1,2* and Jorge Gonzalez Fernandez3

1Department of Legal Psychology, University Abat Oliba (UAO-CEU), Barcelona, Spain

2Department of Criminal Psychology, ESERP Business and Law School, Madrid, Spain

3Department of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences, La Rioja Institute of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences, Logrono, Spain

- *Corresponding Author:

- Bernat N Tiffon

Department of Legal Psychology,

Universitat Abat Oliba (UAO-CEU), Barcelona,

Spain,

E-mail: prof.btiffon@eserp.com

Received date: August 16, 2022, Manuscript No. IPJMTCM-22-14339; Editor assigned date: August 19, 2022, PreQC No. IPJMTCM-22-14339 (PQ); Reviewed date: August 29, 2022, QC No. IPJMTCM-22-14339; Revised date: September 08, 2022, Manuscript No. IPJMTCM-22-14339(R); Published date: September 15, 2022, DOI: 10.36648/2471-641.8.5.27

Citation: Tiffon BN, Gonzalez-Fernandez J (2022) Borderline Personality Disorder, Spiral of Violence, Murder and Concealment of the Body. J Med Toxicol Clin Forensic: Vol.8 No.5: 27

Abstract

A case of the murder of a spouse (domestic violence) where the relationship between both parties, as the person under investigation referred to it was very toxic and harmful due to the severe Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) suffered by the victim. According to the perpetrator, the victim's psychic pathology reached cathartic psycho-emotional peaks of marked hostility and behavioural aggressiveness with heated discussions and escalating conflicts between the two over an extended period of the relationship and for which, in the end, the perpetrator decided to end his partner’s life with an axe. Later, the aggressor buried the body at his own home and kept it buried for about 10 months until it was relocated by the authorities.

Keywords

Borderline personality disorder; Murder; Stabbing; Outburst of rage; Victimization

Introduction

From the juridical-legal point of view, pathological impulsiveness supposes a partial or significant breakdown, if not total of the inhibitory mechanisms of behavior, negatively influencing their cognitive capacities and at the same times their volitional-motivational capacities [1]. From the point of view of the symptomatological phenomenology of psychopathology, impulsive behavior is widely described in clinical doctrine however, said behavioral anomaly is not easy to establish from the juridical-legal point of view. For this reason, the legal operators must know how to appreciate the scope that said pathologically impulsive behavior has in the expression of the criminological behavior, based on the existing indications, the psychological-psychiatric forensic experts and the rest of the burden of proof that is presented. Likewise, juror judgements of the moral responsibility of defendants are significantly influenced by psychiatric information [2,3].

The Case

As stated in the "proven facts" of the sentence, the following is described

“At an undetermined time on an August morning, the defendant, of legal age and with no criminal record, attacked the victim with an axe, hitting her at least 11 times in the cranial area and 3 in the cervical area, thereby causing her death due to neurological injury, secondary to open head trauma caused by the action of the axe, associated with secondary hypovolemic shock.

The aggressor executed the acts being aware that the blows inflicted and the body area to which they were directed would probably cause death and yet he wielded the axe, expecting the death of the victim.

Said defendant struck the victim with the axe, taking advantage of the personal relationship of trust that he had with her, and through a surprise attack on the victim, who was unarmed and alone with the defendant in the house, thus eliminating the possibility of any effective defense and consequently any risk to himself from such.

The victim had been linked in a stable way with the accused in a de facto relationship.

It has not been proven that when the perpetrator struck the victim with the axe, he inflicted unnecessary damage to not only cause death, but also deliberately and inhumanly increase the victim's suffering.

It has not been proven that the defendant provided essential or relevant collaboration for the discovery of the criminal acts carried out by him, through the statement he gave before the judicial authority, by voluntarily submitting to the taking of biological samples, or through the reconstruction of the events that took place.

It has not been proven that said accused proceeded, prior to the hearing, to repair the damage caused to the victim or to reduce the effects of the crime he perpetrated by handing over or making available to the next of kin closest to the victim, the undivided half of two estates of which he was the owner in the town where he lived (a building and a parking space with a storage room), with the intention of unconditionally and irrevocably repairing the damages derived from the criminal act, regardless of whether or not his criminal responsibility was finally declared in the sentence.

At the time of the events, the victim's closest relatives were her mother and her older brother, with whom she did not live and who did not depend financially on her, people with whom she had a distant relationship.”

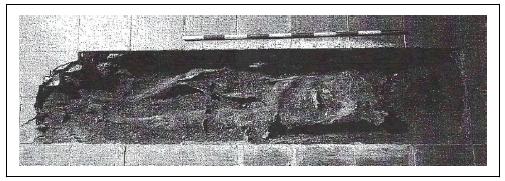

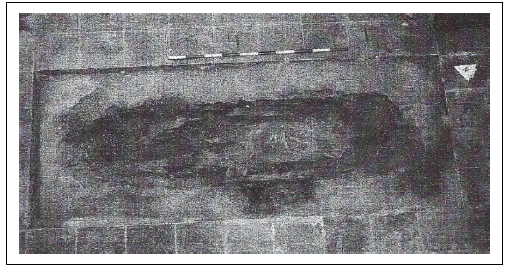

According to what was reported by the perpetrator himself, after killing the victim, the aggressor kept the body in the shower for three hours while he decided what to do with it. Later, he buried the body at his home. Three days after the events, and due to the effect of the corpse's decomposition, it began to swell, displacing the paving stones that covered it. According to the aggressor, he had to remove all the stones again and puncture the corpse's rib cage and abdomen with a knife to deflate it and subsequently level the ground.

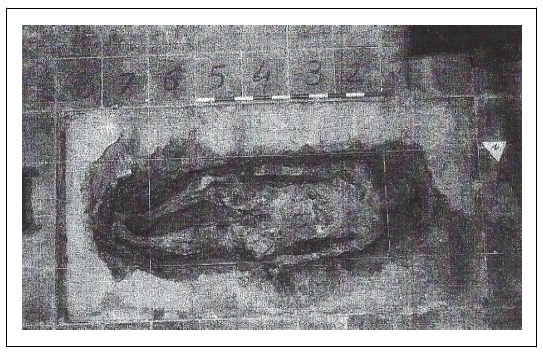

In the meantime, the aggressor reported the disappearance of his partner to the police, keeping the victim buried until ten months had elapsed, the time it took for the authorities to discover the body through relocation techniques and whose remains are illustrated below in Figures (1-6).

Methodology

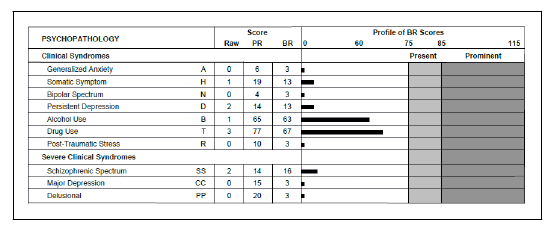

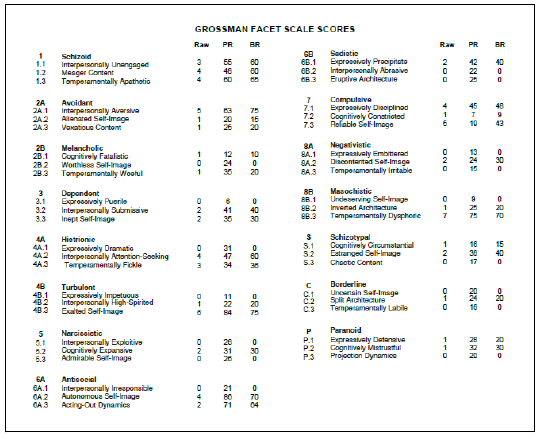

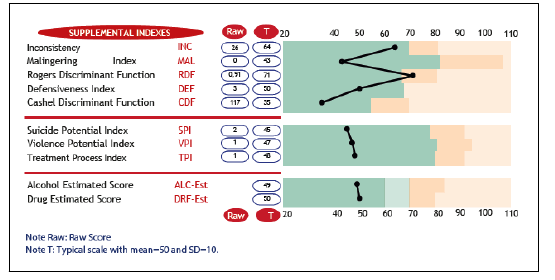

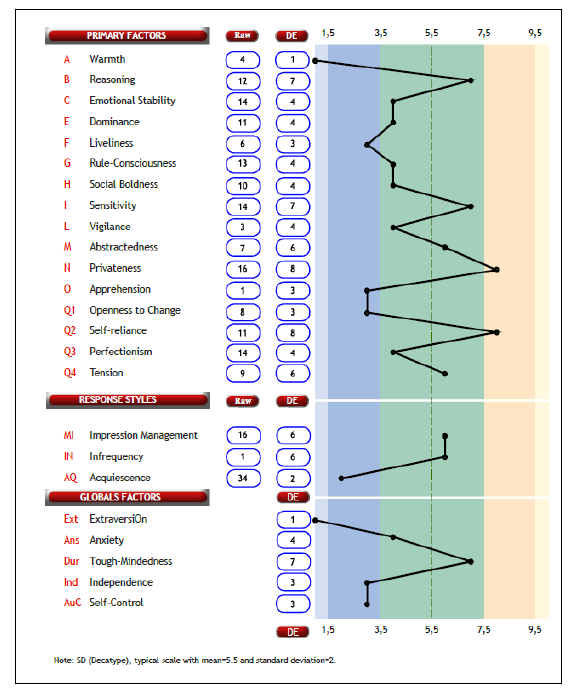

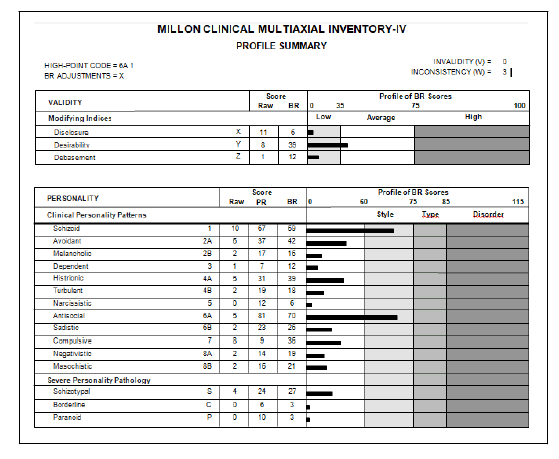

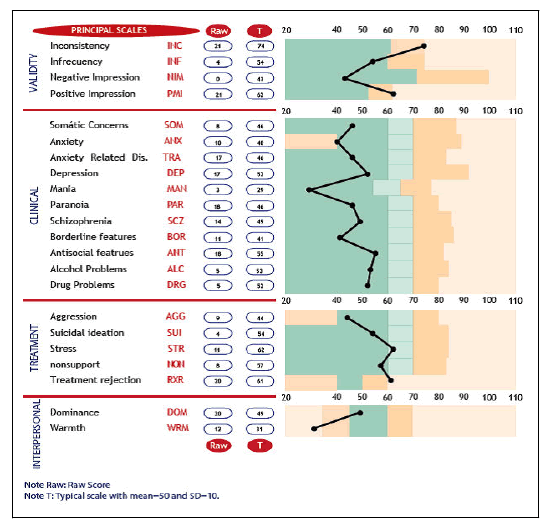

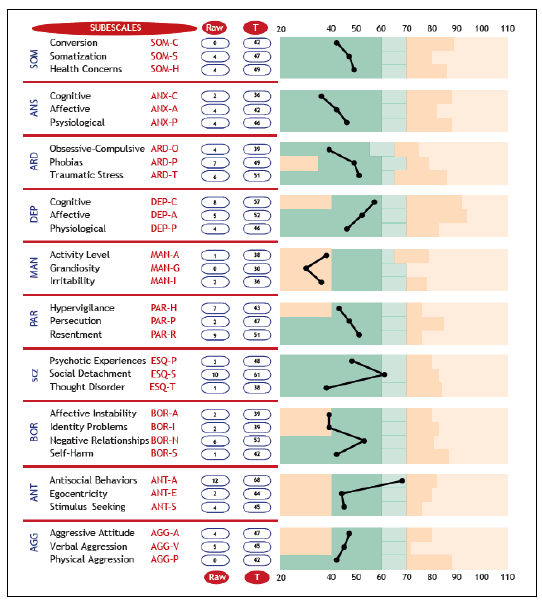

In order to study and analyze the personality and/or psychopathological profile of the accused, the following psychometric evaluation tests MCMI-IV (Millon and Grossman, 2018) and PAI (Morey, 2011) were administered, offering the result of the following Figures (7-14).

Discussion

As stated in the sentence, the accused is sentenced as the "criminally responsible author of a crime of murder, with the concurrence in his action of the modifying circumstance of criminal responsibility aggravated by kinship, to a sentence of 18 years and 6 months of prison, with the accessory of absolute disqualification during the time of sentence and the payment of the procedural costs, also imposing the measure of supervised release for a period of 5 years, which will be served after the custodial sentence and whose concretion will be determined at the end of said prison sentence, based on the danger he poses to society and his prognosis [4-7].

In terms of civil liability, the relatives will be compensated to the value of 95,000.00 Euros.”

Conclusion

From the explanation and clinical-legal analysis of the case, the conclusion can be drawn that impulsivity (pathological) is difficult to measure by mental health professionals who have to make a retrospective inference over time of the behavior manifested in the case at the precise moment of committing the crime.

Likewise, the forensic psychometric evaluation that was carried out much later after the events not only produces results that are not adjusted to the time of the events, but also reflects scores at the time of the evaluation, which differ greatly from the criminological reality of what happened. This is due to the fact that the forensic psychopathological evaluation of the subject (in a preventive inmate regime) was held at a Penitentiary Center, whose modus vivendi is totally different from that of the outside world and therefore governed by behavioral dynamics mediated by this different context.

References

- Tiffon BN, Fernandez JG (2021) Pathological impulsivity of a homicidal juvenile with severe and borderline intellectual functioning. J Forensic Med 6: 1-4.

- Baker J, Edwards I, Beazley P (2022) Juror decision-making re-garding a defendant diagnosed with borderline personality disorder. PPLAFQ 29: 516-534.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Berryessa CM, Milner LC, Garrison NA, Cho MK (2015) Impact of psychiatric information on potential jurors in evaluating high-functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder (hfASD). J Ment Health Res Intellect Disabil 8: 140–167.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Tiffon BN (2015) Los crimenes de perejil. (1st Edition), JM Bosch Editor, Barcelona.

- Tiffon BN (2017) Atlas de psicologia forense (Penal). (1st Edition), JM Bosch Editor, Barcelona.

- Tiffon BN, Fernandez JG (2021) Desperation in major serious depressive disorders and extended suicide risk: A case of double filicide. AJOPY 22: 1-5.

- Tiffon BN (2022) Atlas of forensic and criminal psychology. Taylor and Francis Group, CRC Press, New York.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences